Nature’s Continuum

The composition of plant species in bushland areas, whether they be native or non-native, reflects current and past interactions between:

Different plant communities sit along a continuum of succession. That is, the ordered change from one plant community to another. It is the interaction of the listed factors that can push a vegetation community forward or backwards along this continuum.

A plant community can also sit along a continuum of condition (i.e. level of degradation and health). Similarly, the interaction of climate, soil, water, fauna, fire and human disturbance governs where a site may sit along this continuum from highly degraded to an intact biodiverse bushland area.

A single property may have many sites that sit somewhere on these two types of continuums.

Examples of nature’s continuum

Grassland

Grassland

Grassland remains dominated by grasses and forbs due to factors like, soil, grazing pressure, and fire.

With the absence of grazing and fire this vegetation community can shift from a grass dominated community to one with shrubs and trees.

Wet Sclerophyll Forest

Wet Sclerophyll Forest

Wet sclerophyll Forest is dominated by a canopy of Eucalyptus species and understory of Rainforest species.

This vegetation community forms through the exclusion of fire or reduced fire frequency. Over time Rainforest species will dominate if fire is absent.

Regenerate or Revegetate?

Natural regeneration is the process by which bushlands can recover and restore themselves without direct human intervention.

Where a bushland site sits along the condition continuum, reflects its capacity to naturally regenerate and therefore governs the type of management required to restore or retain ecological health in a bushland area or property.

If the bushland shows signs of good condition, the site has a high capacity to naturally regenerate and may only need low levels of intervention and management to retain the site’s condition (e.g. appropriate grazing management and weed management).

Sites that are highly modified and degraded generally show little evidence or low capacity of natural regeneration. High levels of intervention (e.g. revegetation, ripping the soil, weed management) are required to improve the condition of the site.

Identifying and halting the source(s) of degradation is very important to the success of restoration. This should be the first action taken for the restoration of your site.

The following figure shows the continuum of condition and the restoration approach you can take.

The best way to rehabilitate bushland is to use nature's own recovery capacity.

Building resilience in your bush

Resiliency is the ability for an ecosystem to recover after disturbance. Resilience in species and ecosystems has evolved over thousands, even millions, of years as a response to disturbances such as landslips, floods, grazing, drought and fire.

In simple terms, resilience reflects the ecological health of a site. If the site is in good condition, it can bounce back from a disturbance, rebuilding and maintaining its ecological health and function quickly. Little human intervention may be required to support its recovery.

A site in poor condition can be much the opposite. After disturbance the site is prone to further degradation, which can lead to species loss and impact on ecosystem services like drinking water, food supplies, productive agricultural land etc. Human intervention is required to reinstate ecological function and health. Costs can be high to support recovery of low resilient sites.

It is this resilience that you are working with in ecological restoration.

Before applying any restoration treatment, take time to identify the signs of resiliency and use these as tools to help you reach your restoration goals on your property.

How resilience is expressed may differ depending on the type of ecosystem or vegetation community.

Common signs of good bushland resilience:

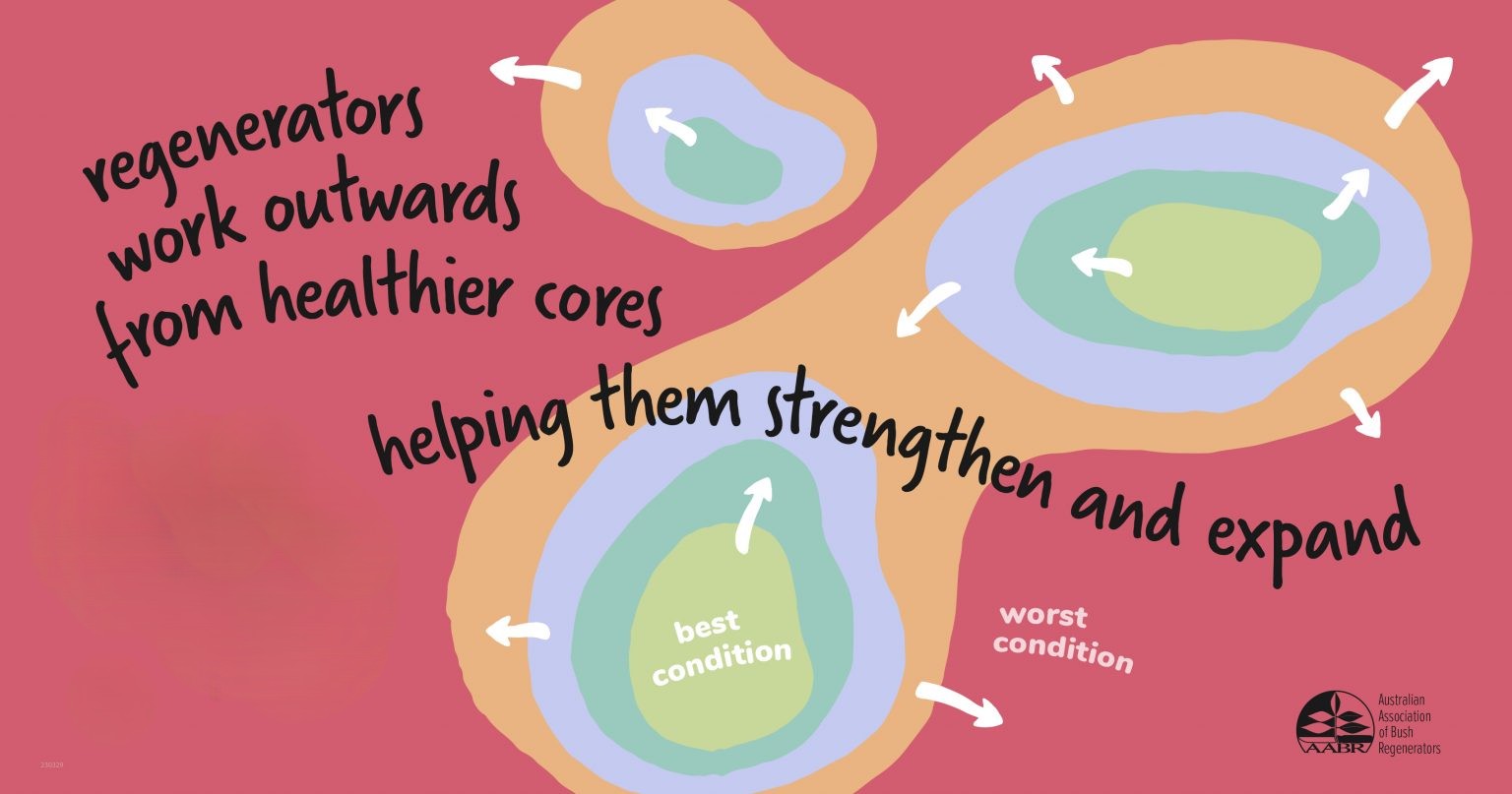

Prioritisation of restoration

Areas in good condition and showing ecological resilience can serve as strong foundations for a gradual restoration program, as they act as natural sources for regeneration and expansion. Even small patches of native vegetation can signal a good starting point. Similarly, a single invasive plant—like an aggressive climber weed—can easily trigger decline and may need urgent attention.

With this in mind, work priorities could be best guided by how much a site is likely to change—with or without intervention. If treating or leaving an area (regardless of its current condition) is unlikely to result in significant change, it may be more effective to assign it a lower priority. However, if intervention could lead to substantial improvement—either by preventing rapid degradation or by supporting broader recovery efforts—then that area should be considered a higher priority.

The most noticeable changes often occur at the edges—where healthier core vegetation meets more degraded zones. Starting restoration in these transitional areas can help desirable species spread into poorer zones and outcompete weeds. If the core areas are relatively intact, working there may not yield rapid results. But if the cores are themselves degraded, they offer the greatest potential for meaningful and fast improvements, making them ideal starting points for restoration.

This information has been adapted from the Australian Association of Bush Regenerators - Deciding on the best treatments factsheet. Resource provided below.

Considering wildlife habitat

Restoring vegetation alone may not fully support native wildlife—especially in the short term. To enhance habitat quality, consider reintroducing key habitat elements such as nesting hollows, fallen logs, and rocks into your restoration site.

While restoration efforts can greatly improve habitat, some actions may unintentionally disrupt existing wildlife use. Understanding how animals interact with the site is crucial, as is not always the way people might first expect. For example, if non-native plants are being used for food, shelter, or nesting, it may be beneficial to retain some patches of these plants until suitable native alternatives are established. If removal is necessary, avoid disturbing these areas during peak nesting seasons—typically spring and early summer.

When clearing large areas of weeds, use a mosaic approach. This allows fauna to continue using undisturbed patches while other sections are being restored, supporting movement and habitat continuity.

Dead trees should be preserved whenever safe to do so, as they offer essential resources like hollows, perches, and crevices for a variety of local wildlife.