This vegetation can be divided into two categories, ‘dry sclerophyll’ forests and ‘wet sclerophyll’ forests.

The main differences between dry sclerophyll forests and wet sclerophyll forests are their ecological characteristics and environmental conditions.

Wet sclerophyll forests are characterised by a dense understory of soft-leaved rainforest shrubs and small trees, occurring in moist situations with high rainfall and moderate soil fertility.

In contrast, dry sclerophyll forests have an open understory with a sparse, sclerophyllous shrub layer, occurring in drier situations with low rainfall and/or low soil fertility.

Canopy varies from 10-30m with a 50-80% canopy cover.

Regional Ecosystems

Regional Ecosystems are a Queensland vegetation community classification system and mapping tool developed by the Queensland Government. It incorporates its regional location, the sites underlying geology, landform and soil and the different vegetation that makes up the ecosystem type. This is a more detailed classification of vegetation communities then the broad vegetation communities outlined in this page.

Regional ecosystems can help you identify suitable species for your revegetation project, help with the planning of fire management, weed management etc., identify the types of fauna habitat and fauna species that may be present on the property and identify which vegetation is regrowth or remnant.

Learn more about Regional Ecosystems – here.

Download your properties Regional Ecosystem map and classification – here.

Regional Ecosystem classification examples for this vegetation community in the Noosa Shire (click to download an RE description or factsheet):

Soil and Geology:

Eucalypt Forest occurs on a variety of soil types from alluvial plains (wetter forests), coastal sand plains, and hills plateau of sandstone dolerite and granite.

Soil type has a big influence on what grows in a eucalypt forest. On sandy, nutrient-poor soils, the understorey is often dominated by hard, tough and sometimes prickly-leaved shrubs like banksias, grass trees and other dry sclerophyll plants. On deeper, clay-rich soils, which hold more nutrients and moisture, the ground cover layer is more likely to be made up of small herbs and grasses. Wet sclerophyll forest generally occurs on deep, well-drained soil like alluvial plains.

Relationship with fire:

Severe fires may slow the growth of trees, but fires of low to moderate intensity (i.e. where there is little or no scorch of tree crowns) will have little effect on the growth of open-forest eucalypt species. Many plant species are fire tolerant, and may possess thick bark, woody fruits, hard-coated seeds and the capacity to re-sprout after fire.

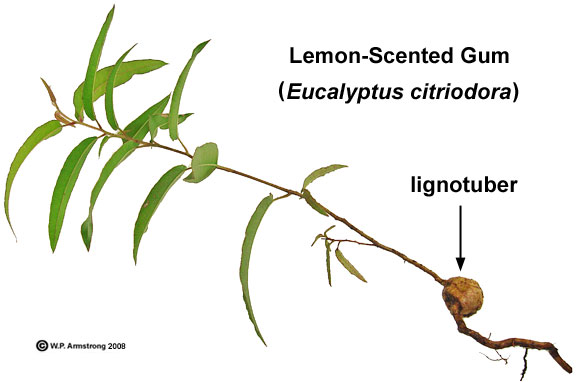

Hollow-bearing trees (living or dead) with senescent crowns are sensitive to fire and are a fragile resource for this reason. Additionally, fire in regenerating forests with a high abundance of seedlings can be vulnerable to fire, particularly for those that haven’t established a lignotuber. Fire should be not applied to these forests until better established.

A grassy understory can be maintained by occasional fire. Burning carried out in cooler or moister periods encourages mosaics which help to retain ground litter and fallen timber habitat.

Exotic grasses including Setaria (Setaria sphacelata), Molasses Grass (Melinis minutiflora) and Green Panic (Megathyrsus maximus) can be a problem along edges and will move into adjacent bushland areas, especially after fire. The seeding period and regeneration characteristics of weeds may need to be considered in fire management to avoid increasing their spread and dominance.

Fire intervals in excess of the recommended interval favour fire-tolerant species, for example the native Blady Grass (Imperata cylindrica), as well as weedy forbs which increase in abundance at the expense of less fire-tolerant species.

Longer fire intervals can result in a gradual increase in abundance of woody species such as some wattles. It is thought that long periods without fire have contributed to the formation of the dense vine forest type understorey present in Tall Open Forest (wet sclerophyll forests). Fire exclusion can also benefit invasive environmental weeds, such as Groundsel Bush (Baccharis halimifolia), Slash Pine (Pinus elliottii), Lantana (Lantana camara) and Camphor Laurel (Cinnamomum camphora).

Resources:

Threats:

This vegetation community has been extensively cleared in our region for agriculture and urban development.

Values:

Noosa Koala Connect

Across the nation, koalas are in significant decline due to incremental habitat loss and fragmentation impacting koala health and survival. The Noosa community recognises the urgent need to protect existing habitat and rehabilitate vital wildlife corridors, to ensure the long-term genetic health of our remaining koala populations.

Noosa Koala Connect is a multi-partner initiative that aims to work with local landholders and citizen scientists to help restore priority koala corridors and find koalas in the wild.

You can play a part in restoring Noosa’s koala landscape. Partner with Noosa Koala Connect to rehabilitate priority corridors and help locate and monitor koalas in the wild.

Management Considerations:

Land managers are aiming to maintain or restore a native species composition indicative to a Eucalypt Forest, protect sensitive and valuable habitat features, like tree hollows, rocky outcrops or fallen timber, and manage pressures such as grazing, weeds or fire to encourage and protect ecosystem values.

Restoration:

Much of our local landscape has experienced significant changes over time, mainly driven by activities such as land clearing for development and agriculture, as well as extraction industries like mining along the Mary River. The growing pressures from urbanisation and climate change have further exacerbated the impact on our local environment.

As land managers, we can play a vital role in helping preserve the health of the natural environment and restore the ecological balance in areas impacted by past disturbances.

What is Ecological Restoration? Here at Noosa Landcare, we like to follow the definition of Ecological Restoration applied by the Society for Ecological Restoration (SER):

“Ecological restoration is the process of assisting the recovery of an ecosystem that has been degraded, damaged, or destroyed.”

There are three main ecological restoration approaches as identified in the National Standards for the Practice of Ecological Restoration in Australia. These three approaches are usually used alone or combined if appropriate for the site. All will require ongoing adaptive management until recovery is reached.

Where damage is relatively low, pre-existing vegetation should be able to recover with threat removed or stopped.

This approach is suitable for bushland areas that:

Weed-free areas of native vegetation | Native species are naturally regenerating i.e. evidence of a diversity of native seedlings and life stages of plants and animals | Mix of diverse native species indicative to the vegetation community(s) present|

Common threat examples:

Storm disturbance – Flood, Rain and Wind damage | Vegetation clearing | Inappropriate fire regimes and wildfires | Inappropriate grazing regimes | Lack of connectivity |

Management action examples:

Fence bushland area to exclude grazing or adjust grazing regime more effectively to minimise risk of over grazing or damage to native vegetation | Develop and implement a fire management plan | Establish connectivity between bushland areas where viable using the reconstruction approach |

Recovery at sites of intermediate (or even high) degradation. Need both the removal of causes of degradation and further active interventions required to trigger natural regeneration and recovery key ecological features.

This approach is suitable for bushland areas that:

Regrowth or recovering vegetation communities | native plant seed is still available on site or will be able to reach the site from nearby bushland areas, by birds or other animals, wind or water | natural regeneration is being inhibited by external factors, such as weed invasion, soil compaction, cattle grazing, mechanical slashing, etc. | Some key ecological and habitat features missing e.g. tree hollows, shrub layer |

Common threat examples:

Inappropriate fire regimes and wildfires | Inappropriate grazing regimes | Weeds and feral animals | Erosion | Slashing and broadscale chemical spraying|

Management action examples:

Integrated Weed management | Applying disturbances such as fire to break seed dormancy | installing habitat features such as hollow logs, rocks, woody debris piles and perch tree | reshaping and stabilisation of watercourses | Remediating soil chemistry and/or soil structure | Identify emerging trees and shrubs and use slashing and brushcutting practices to aid the reestablishment of the native vegetation. Avoid blanket slashing of areas. | Revegetation may be suitable to reestablish species for genetic diversity purposes or that cannot return to site without direct intervention e.g. rare and threatened species.

Where resilience is depleted, and abiotic or biotic elements need to be reestablished before recovery can commence.

This approach is suitable for bushland areas that:

Areas that have experienced significant, long-standing disturbance that the pre-existing native plant community cannot recover by natural means | Significant weed coverage |

Common threat examples:

Inappropriate fire regimes and wildfires | Inappropriate grazing regimes | Weeds and feral animals | Erosion | Slashing | Clearing | Lack of connectivity |

Management action examples:

Revegetation| Integrated Weed management | reshaping and stabilisation of watercourses | Remediating soil chemistry and/or soil structure |

A note on natural regeneration on this vegetation community:

In sub-tropical areas, Eucalypt species do not require fire to release seed, nor do they require disturbance to germinate and establish as a seedling. Seedling mortality can be high in the weeks immediately following germination. Survivorship is largely linked to the development of Lignotubers, formed 18-36 months after germination. The lignotuber contains food reserves and buds which enable plants to reshoot following damage from low intensity fire and browsing. This gives the young trees the capacity to survive and ‘sit and wait’ for an opportunity to grow when a canopy gap is formed.

Eucalypts have long lifespans, so continuous tree recruitment is not needed, as long as sufficient young trees are present to replace old trees, and a seed supply is maintained by retaining mature trees.

The establishment and survivorship of open forest eucalypt seedlings may be reduced or prevented by uniformly high densities of understorey shrubs and small trees such as wattles (Acacia spp.) or weed species like Lantana, as eucalypts are relatively shade intolerant. Though it is important to note that the dense understory is an important habitat feature for small passerine birds, partly due to the reduced abundance of noisy miners. Therefore, we see it beneficial to control dense shrubs to allow tree recruitment only if recruitment is obviously being suppressed or to create a mosaic of sparse (<50% cover) and dense shrub layers within a forest area to maintain bird biodiversity in your bushland area.

Revisit the fire section for information about the role of fire in regeneration in this vegetation community.

A note on managing weeds for this vegetation community:

Many environmental weeds have the potential to invade patches that are close to urban areas especially if the ecosystem has not been burnt for a long time. Common weeds include Chinese Elm (Ulmus parvifolia), Easter Cassia, Camphor Laurel and Broad-leaved Pepper Tree (Schinus terebinthifolius).

It is important to establish a weed management plan for your bushland area to take a strategic approach and be more effective with your resources, including your time.

Please visit our weed management page for more information on weed management planning and weed control methods.

A note on grazing for this vegetation community:

Livestock grazing can be compatible with reforestation in eucalypt open forests, as long as grazing pressure is held at low to moderate levels, and strategic spelling is adequate to allow tree recruitment.

Grazing pressure can impact the diversity of understory and groundcover vegetation. Careful grazing management is required to reduce impact on plant diversity. Particularly with native grasses.

We recommend fencing Eucalypt forests to enable better control of grazing and allow for adequate rest for plant recovery, regeneration and protect vegetation in dry conditions.

A note on enhancing wildlife habitat for this vegetation community:

Tree Hollows:

Many native animals use tree hollows for shelter and nesting, and some also feed on prey found in hollows. Animals that use tree hollows in eucalypt forests include parrots, treecreepers, bats and gliders. The greater glider (Petauroides volans) has one of the highest known demands for hollows of any arboreal marsupial that inhabits eucalypt open forests.

It is important to retain large trees, which are more likely to contain or form hollows, even if dead. Nest boxes can be provided if hollows are absent or scarce. Hollow bearing trees are susceptible to fire, so it can be a good idea to rake litter away from large habitat trees before application of management fires, and to only conduct burns when soil moisture is high.

Fallen timber and leaves:

As the trees grow, they drop leaves, bark and branches to the ground, building up leaf litter. This layer helps protect the soil, keep in moisture and create important microhabitats for many small animals and decomposers.

Fallen timber can provide shelter and feeding areas for birds (Barrett 2000), reptiles, frogs, mammals (Lindenmayer et al. 2003) and invertebrates. A number of bird species such as robins and fantails use fallen timber as platforms to view, and then pounce on, prey on the ground (MacNally et al. 2001). Treecreepers and thornbills often collect insects from fallen timber or the ground nearby (MacNally et al. 2001).

It can be tempting to collect fallen timber for firewood, or just to ‘clean up’, but leaving it (or some) in place will help to retain water and nutrients, and ease housing and food shortages for wildlife.