Waterways and wetlands of the Noosa Shire

Noosa Shire encompasses two catchments, the Noosa River and the Mary River catchment. The Noosa River predominately flows south entering Laguna Bay near Noosa Heads, and the Mary River flows generally north entering the Great Sandy Strait near Hervey Bay. A series of small coastal dunal catchments exist along the coastal fringe and < 1% of the shire is located within the North Maroochy River catchment (Doonan Creek) in the south.

Noosa’s waterways play an important role in protecting biodiversity, providing water for agricultural and domestic use, regulating water quality and quantity, supporting fisheries and providing residents and visitors with a range of recreational opportunities.

Scroll down to learn more about the Noosa and Mary River Catchment.

How rivers work

Catchments are land areas where rainfall collects and flows into streams and rivers, shaping landscapes through erosion, transport, and deposition of sediment.

Waterways vary by bed material—bedrock, clay, sand, gravel—and each type behaves differently, particularly during floods.

Learn how catchments, stream types, and natural processes like erosion and sediment flow influence waterway health.

The Noosa Catchment

The Noosa River flows south from the Cooloola Section of the Great Sandy National Park into Laguna Bay at Noosa Heads.

The catchment covers approximately 854 square kilometres, with a stream network of approximately 1,505 kilometres. This catchment covers 63% of the Noosa Shire.

The Noosa catchment consists of several large and small subcatchments.

These include:

The Noosa River holds some unique natural features. The Noosa Everglades located in the upper reaches of the system, within the Cooloola section of the Great Sandy National Park, is one of only two everglades’ systems in the world, the other being in Florida, USA. It is recognised as a biodiversity hot spot, with over 40% of Australia’s bird species alone using this wetland system. The everglades also provide critical ecosystem services, like carbon storage, flood mitigation, and filtering of sediment and nutrients.

The Noosa River is also one of the few Queensland rivers that receives a continuous year-round freshwater inflow. It has substantial groundwater input from several sources including large sand masses and undulating landscapes that is connected via groundwater through a continuous wetland system which extends up to Tin Can Bay.

The Noosa River system also consists of several shallow lakes. The river was historically shaped by ancient sand dunes. These dunes created natural basins and barriers that hold water, leading to the formation of lakes. The lakes are interconnected through both surface water and groundwater flows. Lakes Cootharaba and Cooroibah are the largest of these, providing large storage areas which slow down the flow of flood water on its way to the river mouth.

The Noosa River was home to the Kabi Kabi Traditional Owner group, who have deep cultural and historical connections to these land and waterways.

To explore the Noosa River Catchment in greater detail, visit the Queensland Government WetlandInfo’s “Noosa Catchment Story.”

This interactive resource provides an in-depth look at the various features of the Noosa River. The Catchment Story was developed with contributions from numerous local organisations and river experts.

Noosa River Waterway Health

Water quality and waterway health monitoring for the Noosa River has been undertaken since 2005. Testing has been completed by Noosa Landcare, Noosa Integrated Catchment Association, Healthy Land and Water and Noosa Council over a monthly and annual basis during this period. Read the latest Noosa River water monitoring and nutrient testing report prepared by Noosa Integrated Catchment Association here.

The data shows the Noosa River is a robust system, but in fair condition. Though large sections of the upper reaches are in near pristine condition, the lower catchment and Hinterland areas become more modified and various levels of degradation are present. Historical clearing in the region has led to narrow vegetation buffers along waterways, that can be fragmented and dominated by invasive species, like Camphor laurel (Cinnamomum camphora). The remaining waterway vegetation is also under threat by the invasive vine species, Cat’s Claw Creeper vine (Dolichandra unguis-cati) and Madeira vine (Anredera cordifolia). These are aggressive climbing vines with the habit of smothering vegetation. They are known as ‘transformer’ weeds in recognition of their ability to transform entire vegetation communities. Once commonly used as an ornamental plant in Queensland gardens, it is now one of the key invasive weed species threatening the integrity and function of our waterways.

Without management, Cat’s Claw and Madeira Vine smothers ground and canopy vegetation, kills trees, exposes waterways to light and increases the risk of erosion.

Due to vegetation clearing and changed hydrologic regimes within the catchment this too has accelerated erosion, particularly on the outside bends of waterways. Bank failure, scouring and stream bed deepening can be observed throughout the catchment. Without woody debris and vegetation armouring and creating resistance against water flow, sediment becomes easily mobile. Fine clay sediment can remain suspended in the water column for a long time and travel far distances downstream. Erosion in the upper reaches of the catchment can have a flow on effect further downstream and in large rainfall events into Laguna Bay.

High sediment loads can smother habitats, like seagrass beds, while also often transporting nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus, which can lead to eutrophication. This process results in excessive growth of algae, depleting oxygen levels in the water and harming aquatic life. For the Noosa River, the area of seagrass within the lower estuary has reduced substantially, has too the benthic invertebrate diversity (1, 2, 3).

Previous studies of water quality within Lake Cootharaba identified flood-derived sediment as the main contributor to high levels of nutrients within the water column, with the Kin Kin catchment being the highest contributor of suspended sediment load to the river’s lake systems (4).

In the Kin Kin valley, the Kin Kin Beds strongly influence the upper catchment of Kin Kin Creek. The Catchment’s steep ranges are comprised of phyllitic shale which are prone to mass failure or landslips during high rainfall events. When mass failure occurs the soil that flows down the hillside from landslips is discharged into the waterway networks and creeks below. This combined with a degraded waterway system, has resulted in high sediment loads flowing into Lake Cootharaba and Noosa River during high rainfall events.

Noosa Landcare established the Keeping it in Kin Kin program in 2017, working alongside Kin Kin landholders and key partners including Noosa Council, the Kin Kin Community Group, the Noosa Biosphere Reserve Foundation and the Queensland Government.

This community soil conservation program aims to protect and restore erosion hotspots identified in the catchment.

Erosion hotspots were pinpointed using LIDAR, which is a remote sensing method that uses light in the form of pulsed laser to measure variable distances to the ground, detecting information about the shape of the land surface. With the help of Healthy Land & Water, an analysis of the calculated differences in the Kin Kin region’s terrain between 2008 and 2015, detected ‘hotspots’ to where soil had been eroded and subsequently deposited during that time frame. Another analysis was then undertaken for 2015 to 2022.

The study showed that for the catchment of only 22,000ha, over 2.4 million cubic tones of soil, or the equivalent of 191,284 large dual axel soil delivery trucks filled with soil, was mobilised between the 2008 and 2015 period analysed.

Efforts are underway to work with landholders to address erosion hotspots and improve the resiliency of the catchment’s waterways and landscape to safeguard it from further erosion, particularly in the face of increased frequency and intensity of high rainfall events due to climate change.

Kin Kin Crossing #3 - High turbidity (sedimentation) after rainfall event.

Keeping soil in Kin Kin

Join the Keeping It in Kin Kin Program and help protect the health of the Noosa River!

Partnering landholders can access financial assistance and expert support to implement practical strategies that improve land and waterway health, including:

- Waterway and gully livestock fencing,

- Installing off-stream water sources for livestock,

- Vegetation planting in waterways, gullies and hill slopes,

- Erosion remediation, and

- Management of environmental weeds, such as Cats Claw Creeper and Madeira vine.

The Mary Catchment

Several of the Mary River tributaries are located in the hinterland regions of Noosa Shire. Six Mile Creek is the largest of these tributaries. Lake Macdonald, the impounded reservoir of the Six Mile Creek Dam, and part of Southeast Queensland’s drinking water supply, is located in the upper reaches of Six-Mile Creek.

Six-Mile Creek is widely recognised for its biodiversity values and intact waterway vegetation and is one of only a few core habitats for the endemic and endangered Mary River Cod (Maccullochella mariensis) remaining. It is estimated that there are only approximately 1000 adult individuals left, with approximately 300-400 located in Six Mile Creek.

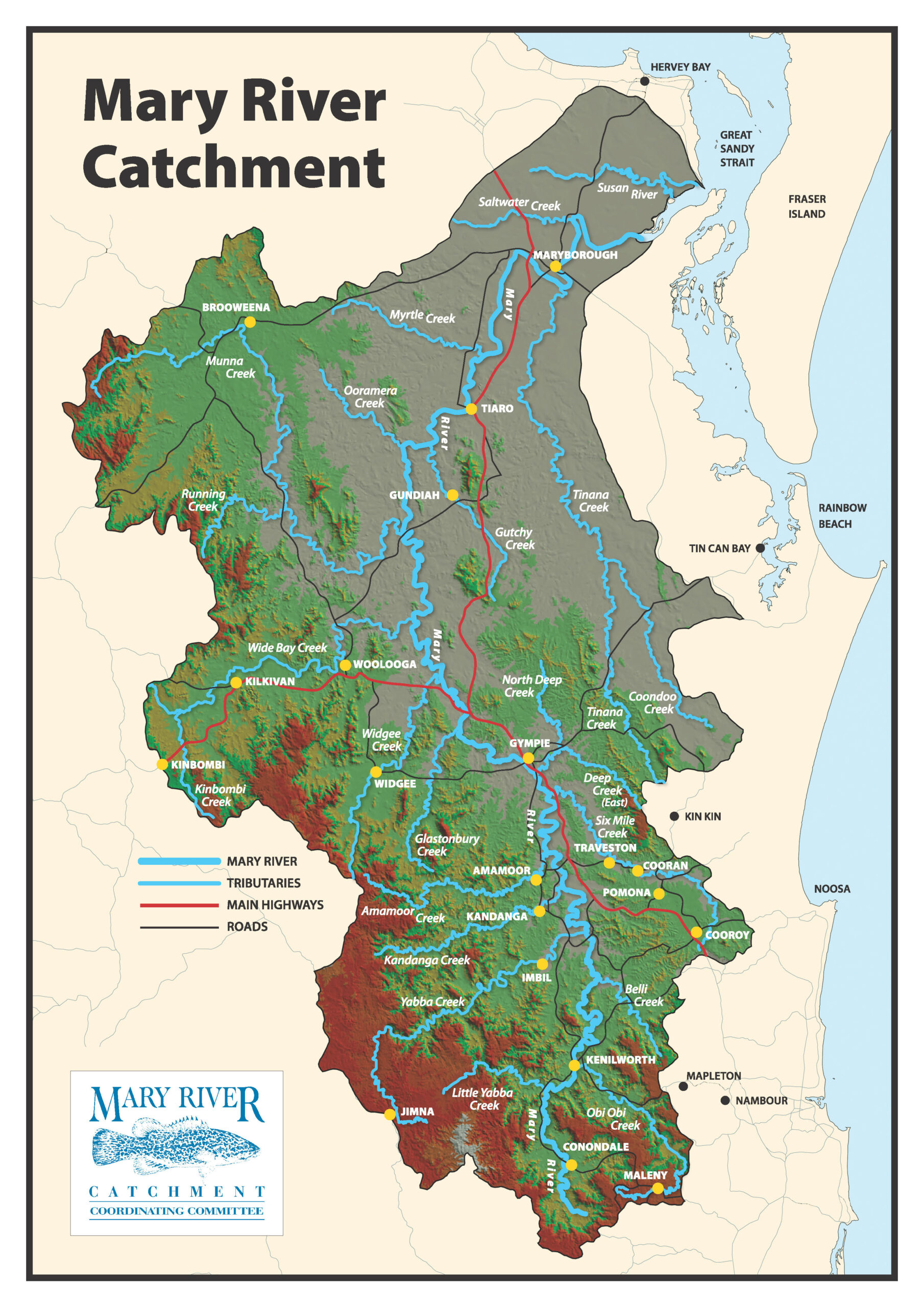

The Mary River Catchment covers 9,595 km² in total. It stretches 307 km from its headwaters in the Conondale Range west of the Sunshine Coast, to its mouth at River Heads in the Ramsar-listed Great Sandy Strait near Hervey Bay. It encompasses a total of 3,000km of major streams.

There are several sub-catchments within the Mary River Catchment.

These include:

The Mary River is one of the 35 river catchments that flow into the Great Barrier Reef. It plays a vital role in the health of the Great Barrier Reef due to its contribution to sediment and nutrient loads. The Mary River is the fourth highest contributor of fine sediment to the Great Barrier Reef.

The legacy of historical mining and land clearing combined with pressures of an increasing population, and a changing climate continues to pose challenges for stream bank stability and water quality for the catchment.

The Mary River Catchment is home to several Traditional Owner groups who have deep cultural and historical connections to these land and waterways. These groups include:

To explore the Mary River Catchment in greater detail, check out the Queensland Government WetlandInfo’s “Walking the Landscape: Mary River Catchment Story.” This brief video provides a comprehensive overview of the various features of the Mary River. This “Walking the Landscape” was developed with contributions from numerous local organisations and river experts.

Mary River Waterway Health

The health of the Mary River is essential due to its influence on the Great Barrier Reef and being home of several endemic and endangered species, including the Mary River turtle (Elusor macrurus), Mary River cod (Maccullochella mariensis), and Australian lungfish (Neoceratodus forsteri). Furthermore, it plays a vital role in our community by supporting local agriculture, contributing to the Southeast Queensland water supply, and sustaining both commercial and recreational fishing in the lower reaches.

In the early 1990’s, the Mary River was described as one of the most degraded river systems along the east coast of Australia. Since European settlement in the 1800’s it has been subjected to immense pressure from land clearing, gold mining, industrialisation, sand and gravel extraction and increasing demand for rural and urban water.

Poor riparian vegetation and streambank erosion is common. The majority of streams in the catchment are considered to be moderate to poor in terms of channel diversity and aquatic habitat. The Mary River is the fourth highest contributor of fine sediment to the Great Barrier Reef. In a study conducted in 2002, the catchment was estimated to contribute approximately 500,000 tonnes of sediment per year to the coastal waters (5). The primary sources of this sediment being from streambank and gully erosion.

These high sediment loads wreak havoc on the health and survival of coral reef and seagrass habitats by reducing light penetration, smothering and adding excess nutrients to these valuable ecosystems.

The significant streambank erosion of the Mary River also alters the physical structure and ecological function of the river system. Streambank erosion leads to the retreat of riverbanks, causing the river to widen and straighten, impacting flow dynamics and stability. This also has a flow on effect, impacting instream habitat features and putting pressure on remaining vegetation along the banks. Not to mention the loss of productive farmland impacting our community.

It isn’t unusual to come across bare vertical banks along the river reaching up to 15m high in some areas. Erosion hotspots along the Mary River are primarily concentrated in the Upper Mary Valley. It includes areas along the Kenilworth and Mary Valley reaches of the Mary River, Elaman Creek, Obi Obi Creek, and Kandanga Creek.

Over the past two decades, remediation works have been undertaken to help tip the scale on erosion and create a more resilient and stable river system. Mary River landholders, the Mary River Coordination Committee (MRCCC) and a suite of partners, have undertaken extensive large scale riverbank restoration works.

The installation of Pile Fields has been an important tool in helping provide bank stability to high priority erosion sites along the Mary River. This involves the reshaping of the eroding ‘cliffs’ of the streambank, driving timber pile from the toe of the bank up and further armouring the toe with rock. The pile logs and rock provide the vulnerable bank some stability, help slow water down and encourage deposition, while the planted native vegetation becomes established and will provide the long-term stability for the bank.

Although the vegetation takes time to reach a level of maturity, structural diversity and robustness that allows it to perform its desired erosion control (and other) functions, the timber pile fields provide protection in the meantime, decaying after 10 – 15 years, by which time the riparian vegetation is established.

This new engineering solution and extensive revegetation has successfully reduced bank erosion by an impressive 85% during the 2022 floods, compared to past data (6).

Reviving Queensland’s Mary River (and Great Barrier Reef) with environmental engineer Misko Ivezich

Establishing vegetation along the Mary’s banks and within its channel is the best long-term solution to build resiliency and protect its waterways from further large-scale degradation.

A healthy riparian zone consists of trees, shrubs, grasses, sedges and reeds in the stream, on the banks and on the stream margins. Together they help reduce flow velocities, directly reinforces riverbanks, and intercept and slow surface runoff. Each type of vegetation also plays an important role in helping protect the bank from the different erosion processes. For example, canopy vegetation has a greater influence in reducing mass-failure. However, shrubs and grasses on the bank face, and sedges and reeds at the bank toe, are equally important for controlling bank scour.

Below is a pile field installation to remediate a 15m+ eroding bank along the Kenilworth stretch of the Mary River.

Beyond sediment, habitat degradation is one of the primary threats to threatened species, the Mary River cod, White-throated snapping turtle, Australian lungfish, and the Mary River turtle.

Key habitat features critical to the health of these species include:

Invasive species like tilapia, sooty grunter, and foxes are putting further pressure on the river’s native species.

Tilapia, in particular, have rapidly proliferated in the river system, competing for habitat and food with native species and sometimes preying on their juveniles. This competition has led to a decline in the numbers of some native species, making conservation efforts more challenging.

MRCCC, working alongside a many stakeholders including Burnett Mary Regional Group (BMRG), Griffith University, Tiaro and District Landcare Group, Kabi Kabi Peoples Aboriginal Corporation, Jinibara Peoples Aboriginal Corporation, Butchulla Native Title Aboriginal Corporation, Seqwater and Noosa Council are working hard to help protect Mary River’s threatened species.

Alongside valuable streambank rehabilitation works, monitoring of turtle nests, nest protection and fox control, and habitat creation through the installation of ‘Turtle Pots’ are recovery actions underway to help protect and improve local populations of the critically endangered Mary River turtle and white-throated snapping turtle.

MRCCC, Griffth University and BMRG also establishing a unique hollow log habitat design to install in important streams of the Critically Endangered Mary River Cod. These are designed to replace the missing woody debris that once were a common feature of many of our river systems pre-European settlement. These ‘Cod Logs’ have already shown great success, with cod spawning recorded for one installed hollow in the first year of installation. Cod hollows weren’t just enjoyed by cod; a plethora of other species also made themselves at home including Saw-shelled turtles, Eel-tailed catfish, Longfin eels and Eastern water dragons. Learn more about the Cod Logs, including amazing video footage of Mary River Cod protecting its eggs, here.

Efforts have also been made to rehabilitate valuable instream vegetation, particularly after major flood events. Trials have been undertaken for rehabilitation methods for Vallisneria, a native aquatic plant and important breeding habitat and food source for the Vulnerable Australian Lungfish.

Together, these actions are delivering meaningful, measurable benefits for the survival of these threatened species, as well as many other species that depend on the Mary River.

We can’t forget about our wicked waterway weeds. Invasive plants are also a significant concern for the Mary River ecosystem and its health. Cat’s Claw Creeper vine and Madeira vine are aggressive climbing vines with the habit of smothering other vegetation. They are known as a ‘transformer’ weed in recognition of their ability to transform entire vegetation communities. Once commonly used as an ornamental plant in Queensland gardens, it is now one of the key invasive weed species threatening the integrity and function of our local waterways.

Without management, Cat’s Claw and Madeira Vine smothers ground and canopy vegetation, kills trees, exposes waterways to light and increases the risk of erosion.

Restoring Life in Our Rivers

Healthy waterways play a crucial role in maintaining ecological balance and supporting a thriving community.

Within the Noosa Shire our community has been working together over many decades to help turn the tide on degradation and restore life back in our local waterways.

Do you have a creek on your property? Explore practical tools to assess and improve the health of waterways on your land.